Artist John Scane - Press

Currents: A Group Show

November 2015

Artists deal with human issue just like everyone else, except, being visually-minded, they make their thoughts accessible to all who can appreciate their meaning. Katie Stubblefield is drawn to that moment when things shift, the cliff hangers of life when events suddenly are no longer the same. Working with various artistic disciplines, her metaphors embrace imagery inversion from methods of horizontal and vertical processes. The final canvas captures a movement with no direct destination, a sense of uncertainty. Tom Dowling observes that when he lived in Italy he saw aspects of himself that did not appear in his home base. His paintings combine the ambiguity of two and three-dimensions, and in a few works he places a rod in front of the canvas to add a distinct line that seems to separate and guard the image behind.

Jane Bauman and David Michael Lee each honor their late fathers. Bauman represents her Dad’s love of plants and her love of him by digitally printing scenes from famous gardens and placing over the reproducible photographs a painted Rorschach image as she marries technology with one of a kind traditional paint. Lee uses black hemp fabric his father left him as sources for his art. He sculpts each canvas rounding out its bulging surface while painting living shapes and patterns that seem to breathe in and breathe out existing in their hemp world. Yevgeniya Mikhailik uses clay board to find hidden white lines within an image. While in others she paints thin black lines on the image. Her concern is memory of places and her many relocations in life. Finding and adding lines are her way of describing her need to continuously restructure life to relate to new places. John Scane entitles his body of work “Houses.” It is about remembering people he met at various ages, like the different personalities of houses where assorted people lived. He looks at relationships through color, shape, brush strokes, texture, palette knife and scraping. The painting relationship symbolize the many relationships that come and go and the memories of various people. Scane’s work gently invites the viewer in, drawing us into a world of subtleties where his palette becomes a well to dive into and explore one artist’s personal view of life. Ann Marie Rousseau searches all types of gestures of lines. Endless investigations continuously excavates new forms of linearity. Her lines are getting more expressionistic, converging into rope-like depictions of a chalice, a cup and stem, having endless references. Apparent too are the many hand and body movements that go into her large drawings, sweeps of muted color, and graceful choreography that convey a compelling energy that radiates from her energy and her linear works of art.

-Roberta Carasso-

Launch LA: “Before Present” by William Wray and “Houses” by John Scane

At first glance little similarities exist between Wray’s raw streetscapes and Scane’s non-objective patchwork arrangements, yet at their roots, both bodies of work are quite similar: both artists were trained and worked in the figurative arts and eschew more and more of these rules for the freedom inherent in abstraction. Through their processes both artists find experiences and memories that inspire them and then work to trim away as much extraneous visual detail as possible from these without destroying their substance, until what remains is a purer communication – an idea compressed into the simplicity of shape and shade.

Before Present captures the haphazard and gritty beauty of California’s urban sprawl, grasping just the right lighting and vantage point for each scene. No subject is too humble: whether it be a dilapidated gas station, the gleam of a sodium streetlight in the brash angles of an all-American ’80s muscle car, or an unadorned side view of a ’60s suburban home, Wray taps into each subject and distils their aesthetic merits and emotional resonances into a powerful and heady essence. A sense of fondness permeates, a sense of Wray’s appreciation and even fondness for these bedraggled places.

This alchemical process which transforms the commonplace into the extraordinary is mirrored in Wray’s technique: “Using a utilitarian working-man’s aesthetic inspired by my subjects, I paint on wood panels from home depot and use cheap plastic brushes from the hardware section of Ralph’s to prevent the refined rendering that using a sable brush encourages.” Breaking his subjects down into abstract shapes, Wray strives for a perfect balance of “realistic abstraction” – viewers can identify the scenes and objects, yet a strange haziness dominates his works, blurring edges and the delineations between shapes. Stepping closer exaggerates this effect, each object drifts apart like water in oil into strangely satisfying smears of color and texture. As is the case with memories, with prolonged contemplation the detail in Wray’s paintings fades into vague impression which against the odds bear all the weight of feelings and significance.

Scane’s Houses embraces a satisfying simplicity both in terms of its palette and forms that belies the depth of its subject matter. “The ‘Houses’ series is about relationships: personal relationships with family and friends as well as formal relationships of color and composition. Both kinds of relationships change over time, and both seem to be intertwined to me,” explains Scane. Like Wray, Scane is driven by his personal experiences – each painting begins with the memory of a house, the relationships it represented, the lives and moment that unfolded within. As paint is added, pushed and drawn across his canvas, these memories well forth and recede again with successive layers as forms emerge, guided more by feeling than a desire to duplicate the physical reality of these houses.

The images are composed of segments of color in which muted blues, greens and purples predominate, arranged in what initially appears a purely abstract manner. Their shapes possess no clearly defined edges, their lines waver and their colors meet to metamorphose into another shade or to clash jarringly with an adjacent field of contrasting color. Yet closer inspection brings out more literal possibilities, as Scane puts it: “Architectural and landscape views combine, hovering between street level and bird’s eye views, creating a pictorial space that is at once flat and illusionistic.” Entertaining this perspective, in one painting a rectangular yellowish shape leaps forth, becomes an open doorway; warmth and light spills invitingly out into the night. This is the gateway, shapes become not just houses, but homes, bearing the marks of their inhabitants, their families and histories in an intuitive code of color and light.

John Scane

John Scane was born in Los Angeles in 1967. Spending the first year of life as a foster child Scane was later adopted by his foster parents and raised in the small town of Glendora in Southern California. After attending California State University Long Beach, Scane became active in the Los Angeles art scene. Trained primarily as a painter Scane has expanded his skills to include photography, design, woodworking and sculpture. For 15 years he owned his own woodworking business where he designed and built many custom furniture pieces. He has exhibited his art nationally and internationally, received a generous amount of press and has his work in many private collections. In 2003 he co-founded the artist group Pharmaka that is based in Los Angeles.

William Wray

After a nomadic childhood traveling the world William Wray began working in the animation business as a teenager, eventually enrolling in The Art Students League in New York to study fine art in the late eighties. Not empathetic to the conceptual art world all around him in Soho, William went back to work in the commercial field. He is best known for his painting style on the Ren and Stimpy Show, comic books and his work in Mad Magazine.

After a concentrated series of oil painting workshops over the last ten years and a maturing reformation of his realistic art style into a more abstraction based approach, William has turned his attention to documenting the decay of the urban environments in California which he grew up with – the focus of his 2015 Launch LA show ‘Before Present’.

-MARCH 10, 2015 by FABRIK-

About the Life During Wartime series.

John Scane’s Life During Wartime series of paintings examines themes of violence, patriotism, disconnection, and virtual reality through the lens of the video game. This series establishes a new mode of painting that might be called ‘Virtual Realism’ because it uses some of the traditional strategies of realist painting but rather than applying them to the natural world it takes the artificial, digital, virtual world of online computer gaming as its subject. These paintings present a new and unique way of communicating about the virtual and real worlds- through the archaic process of painting, Scane analyzes the strange world of online gaming and the mediated human interactions between gamers.

Popular online games often mimic recent and ongoing military conflicts, creating a richly realized virtual facsimile of the real world. In this way a kind of non-physical parallel plane of battle, a ‘virtual theater,’ has been created. It is within this digital virtual theater that participants experience seemingly real events and interactions taking place across vast distances of physical space, across borders and nations, blurring the lines between nationalities and time zones. These simulations of real war feed contradictory feelings of competition, domination and bloodlust as well as teamwork, accomplishment and camaraderie. The experience facilitates a profoundly obscured distinction between reality and fantasy, which is mirrored in both form and content of these contemporary paintings.

Imagery from the Life During Wartime series is executed in a warm tone overall, suggesting the yellowish glow of Old Master paintings or the patina of age which reinforces the historical references to European paintings of battle across the centuries. In fact, for Scane, the whole endeavor has become as much an examination of the history of war paintings as it is an exploration of computer-based games. The resulting narratives and situations are at first familiar yet become more ambiguous as one continues to look: the viewer will find there is no specific story being told, rather a suggestion of something subtly bizarre, somehow both sinister and humorous. While the imagery and composition of these paintings reference classical painting, historic photographs, recent events and familiar subjects, the viewer is left wondering what exactly is taking place; teams are mixed, notions of good and bad are absent, expectations are thwarted and intentions are blurred. We are left with an absurd and somehow tragic non-space, obfuscated by both technology and human imperfection…kind of like war.

-Vonn Sumner-

Huffington Post

Haiku Reviews, January 2013

John Scane and Vonn Sumner both concern themselves with the human figure, isolated and striking out as best it can in seemingly hostile contexts. Their renderings of the figure are as stylized as their settings, and one comes to realized that Scane’s, at least, are based on semi-realistic video war games, while Sumner’s, more graphically direct, suggest children’s-book illustrations. Scane exploits the photographic “naturalism” that video games depend on – or, rather, aspire to but can’t quite achieve. Indeed, Scane is sensitive to the slippage that pertains in these games between picture and action, and manages to paint “between” the reality of photo-reportage and that of the computer screen. This stage of perception is where we all now “see” our news, so Scane’s renditions of street soldiers and riot police seem unusually vivid. Sumner’s approach is more obviously metaphorical, if not allegorical, and also more charming in its absurd and surrealist touches. His figures are no less bellicose than Scane’s, but a lot less credible as “real” and more absurd. They feature men in business dress brandishing improvised weapons but engulfed in floods or lost on some sort of oddly lit stage, and sometimes masked in silly excuses for balaclavas. The two painters cultivate the grotesqueries of conflict like gentle moralists, mocking (and thus warning against) the pretension of human aggression. (Brett Rubbico, 361 Old Newport Blvd., Newport Beach CA)

-Peter Frank-

Poets/Artists

December 2012

OF WAR AND WARRIORS: VIRTUAL REALISM and THE ART OF JOHN SCANE

In retrospection the vagaries of history, of life have always been best defined by artists, whether in the written word of poetry and memoir and fiction, or in the constructed sculptural or architectural monuments to battles or heroes or the horror of mass destruction, or in the paintings of artists who have attempted to make visual the madness and the pity of war. And yet we iterate, as though time and the presence of historical space pleads a case for disregard. Children make war games as though that urge for combat is genetic, and now with video games replacing yesterday’s toys, men and their kin can recreate battles and slaughter and implosions in an atmosphere of competitive entertainment.

But such disregard for truth is at the core of the current paintings of John Scane, a Los Angeles artist who is responding to the global combative crises with conviction and using this apparent disparity between video game fantasy fulfillment as a means to address the disparity between the violence and horror of war and the popular use of combat as a way to be entertained, to remain distanced. Scane is a realist painter, an artist capable of factual representational art. He paints in oil on canvas in a traditional manner and it is this gift that enables him to pull his audience into his paintings and challenge them to decipher the thin line between picture and reality.

Juxtaposing the theatrical super heroes of video war games with images gleaned from the immediacy of actual battles and fighting in action, courtesy of the availability of the Internet and clicks on the YouTube bringing such realities into our homes, Scane admixes our entertainment preoccupation with the moments of watching men/women/children dying from bullets or drones or suicide bombers. His paintings at once imitate and recreate war as those who have not experienced it can attempt to understand: standing before his canvases the viewer can readily relate to the clicking and moving of imaginary soldiers in virtual time to defeat the aggressors allowing that sense of heroism, patriotism, subliminal sociopathic/psychopathic urge to kill for enjoyment, competition, and camaraderie. Until the threshold is crossed.

John Scane, then, makes war visual, the terror accessible, related to famous paintings of the past by artists who dealt with war, artists such as Gericault, Goya, Thomas Waterman Wood, Peter Rothermel, George Edmund Butcher. He seduces the viewer by creating near cartoon images, such as the ones with which we feel comfortable in a video game, and by making them like objects of malleable moveable entertainment pawns, the warriors implant on our minds and suddenly the connection to what is happening in real time results in an interaction of recognition that war is happening and that we are not watching a screen or a proscenium arch or a painting. We are participating, if only as an observer, in war. The jolt is intentional: Scane causes a heightened awareness of ourselves, our immediate and distant world, and our strangely subservient participation not in playing at war games by escaping into the false virtual, digital world, but by failing to respond appropriately to that human reality of war.

Artists, such as John Scane accomplish this mission using their own particular technical language. Instead of settling for our shaking our heads in sorrow, in disbelief when we encounter such anti-war works as Benjamin Britten’s massive and pungent War Requeim, the words from World War I poet Wilfred Owen, he asks us to stare and be aware and even perform that response all artists desire – to respond and act.

-Grady Harp-

ArtScene

November 2012

The quirky exhibition entitled "War Paint," featuring John Scane and Vonn Sumner, is particularly smart because it engages the subject of war without being preachy and overbearing. The gallery displays John Scane’s images to the left and Vonn Sumner’s on the right, but the twisting layout forces us to interact with both sets of images. Much like a fistfight, my head was on a swivel as I took in many curatorial decisions that played the imagery off on another. Scane’s imagery appears to be the more serious compared to the illustrative and narrative vision of Sumner. One painting by Scane, entitled “You,” features a gun held in a first person perspective, much like a video game. In our field of vision we look directly at the back of a soldier who seems to be leading us, the distance fading away into a mist of gray. The image is not haunting but a bit disconcerting, and manages to balance an aura of respect with a healthy level of distrust. In contrast, Sumner’s work is more stylized and lighter in its tone. His isolated figures carry trashcan lids used as shields and makeshift spears as though they are playing at war. Recalling imaginary battles as a child, a particular adult figure is often repeated in various compositions with dramatic poses. It’s as though we entered in the middle of a story. The show shines in its curatorial decisions. The dramatic is mixed with the playful for an enriching effect (Brett Rubbico Gallery, Orange County).

-G. James Daichendt-

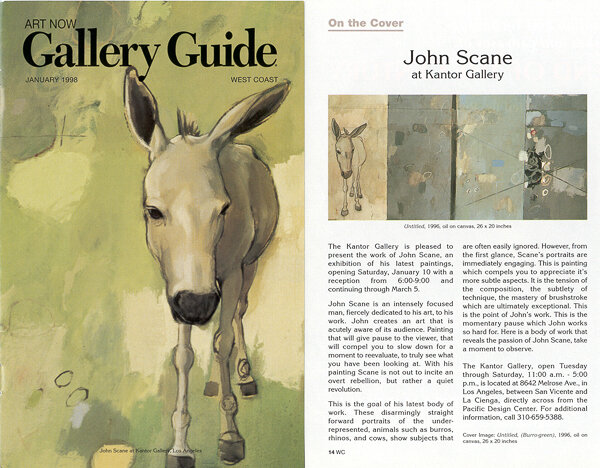

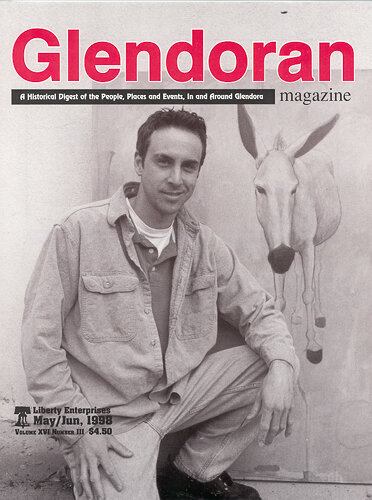

Scane Steals the Scene

Artist John Scane’s slide lecture at Weingart on March 22 traced his journey from obscurity to the vanguard of L.A.’s art scene. Leonardo DiCaprio and Seal have bought his paintings, which share space in the Kantor Gallery with Andy Warhol’s.

The key to his success: Donkeys. He paints realistic donkeys in abstract backgrounds. Is it social commentary? Subtly religious? The art world has its interpretations. Scane said he came across the burros on the beaches of St. John in the Caribbean. He put them in his paintings and won over art critics and collectors. The donkeys are Scane’s trademark—in spite of himself. He explained that the background compositions, which show displaced nature, are the focus of his paintings.

Despite numerous commissions to paint new works that feature the donkeys, Scane treats every painting as if it’s a new subject. He needs to find something interesting in it.

"When I’m working, I’m looking at pigment and oil to put on a flat surface the best I can, to say something that would mean something to someone," he said.

Though successful, Scane is uncomfortable in the public eye. He is reserved and prefers to communicate through his art.

"I wouldn’t know how to play to an audience. It’s like getting people to like you, and you can’t. As long as I know the work is good, I know that other people will. Maybe not the general [public], but there are always people to trust in their judgment," he said.

Scane added that the donkeys are also the worst part about his success. It becomes an expectation. So, unafraid to try something new, he is moving from donkeys to trees. A kind of obsession with trees has gripped him. Aside from painting them, he has started dabbling in woodwork. Scane’s furniture has an Oriental simplicity, and though he hasn’t achieved success as someone who makes furniture, he enjoys the work.

"Not everyone needs a piece of art, but everyone needs a table," he said. Paradoxically, by making the table a piece of art, he makes art accessible.

Woodworking has substituted Scane’s spontaneity with method; one needs patience and persistence to think everything through. He said that paint can be scraped off a canvas, but woodwork is unforgiving.

In an interview, Scane offered his answer to the ancient question, "What is art?"

"My definition of art," he said, "is communication… but that’s too simple. [But] it is my way of communicating."

Scane seldom titles his artwork. He feels it would limit what the viewer sees. "If I titled my work, I’m telling you what to see in it," he said.

-Marcus Gaulberto-